Guide to Sento: Understanding Japanese Bathhouses

What Is a Sento? Your Complete Guide to Japanese Public Bathhouses

Japan is a country where the bath, a daily necessity, has been developed almost into an art form. Because of this, sento, or Japanese bathhouses, are a cultural experience that visitors should definitely experience. These public baths are a welcoming slice of everyday Japan and have been important community hubs for centuries, as spaces for relaxation and social connection.

The image of Japan’s bathing culture often conjures up luxurious onsen in scenic countryside scenes, but sento are still rooted in the simplicity of daily urban life. However, did you know that traditional sento murals often feature Mount Fuji? This artistic tradition began in the early 20th century to give bathers a sense of escape from city life, so, in a way, scenic landscapes undoubtedly remain an aspirational sight during a bath. But their convenient urban locations allows us to enjoy this simple pleasure, often just a few minutes walk from home.

What Is a Sento Bath?

A sento (銭湯) is a public bathhouse where locals come to relax, socialize, and soak away the day’s fatigue. Unlike onsen, which use natural hot spring water, sento rely on heated tap water, making them widely accessible in urban and suburban areas.

Stepping into a sento, you’ll typically find a gender-segregated layout, with changing rooms leading to spacious bathing areas. The baths themselves vary in size and style, ranging from simple tiled pools to more elaborate options featuring jet streams, cold plunges, or even medicinal herbs. Some local sento may also have sauna spaces or other facilities such as massage chairs.

What Is the Difference Between a Sento and an Onsen?

While both sento and onsen are central to Japan’s bathing culture, they differ in significant ways. As mentioned already, the most notable distinction lies in the water itself: onsen use natural hot spring water that is geothermally heated and often infused with minerals, which many believe have therapeutic properties. Sento, on the other hand, use tap water that is heated, making them more accessible and not tied to specific geographic locations.

Because of this, their purpose is another key difference. Onsen are often found in resort areas and serve as destinations for relaxation and travel, frequently paired with ryokan (traditional inns) or scenic views. Sento, by contrast, are community-based and located in urban or suburban neighborhoods, functioning as affordable public facilities.

This is why, despite being similar at a fundamental level, both offer unique experiences: onsen are ideal as a holiday retreat, indulging in Japan’s natural beauty, while sento provide an authentic window into daily life and local traditions.

Can Foreigners Go to Bathhouses in Japan?

Absolutely, foreigners are welcome at sento across Japan. For some, the experience may feel intimidating at first if you’re unfamiliar with the customs, but most bathhouses have visual guides or even signage in English to help visitors navigate the process. Staff are often accommodating, and some modern sento are designed with tourists in mind, making them more approachable for first-timers.

However, super sento or spa-oriented sento (larger, more modern facilities often designed with leisure and luxury in mind) may have stricter policies regarding tattoos. Some of these places might request tattoos to be covered with stickers or bandages (if the tattoo size is not too large), for instance.

A Brief History of Sento

The origins of sento trace back over a thousand years to the Nara (710–794) and Heian (794–1185) periods, where they were influenced by Buddhist purification rituals and the cultural notion of purification in Shinto. Initially found in temples, these bathhouses were primarily reserved for monks and the elite. It wasn’t until the Edo period (1603–1868) that sento became widely accessible to the public, developing into neighborhood hubs in urban centers like Edo (modern Tokyo) since most homes did not have a private bath.

During the post-war era, sento reached their peak, serving as essential facilities for communities rebuilding their lives, as the widespread destruction created an even greater need for public baths.

However, with the rise of private bathrooms in Japanese homes during the late 20th century, the number of sento began to decline. Despite this, their cultural significance remains strong, with many modern sento preserving traditional elements while adapting to contemporary needs.

Are Bathhouses Still a Thing in Japan?

Yes, but their role has evolved over time. In the past, when private baths were uncommon, sento were essential for daily hygiene and social interaction. However, as more Japanese homes were equipped with baths after World War II, the number of sento began to decline. Despite this, bathhouses remain a cherished part of Japanese culture, particularly in urban areas where they offer a space for relaxation and connection.

Today, sento are experiencing a modest revival. Many are embracing creative designs or offering modern amenities like saunas and jet baths to attract a new generation of visitors. Some even double as community hubs, hosting events, art exhibits, or yoga classes. Local neighborhood sento continue to serve residents, while larger super sento cater to tourists and families with upgraded facilities.

What to Expect at a Sento Bathhouse

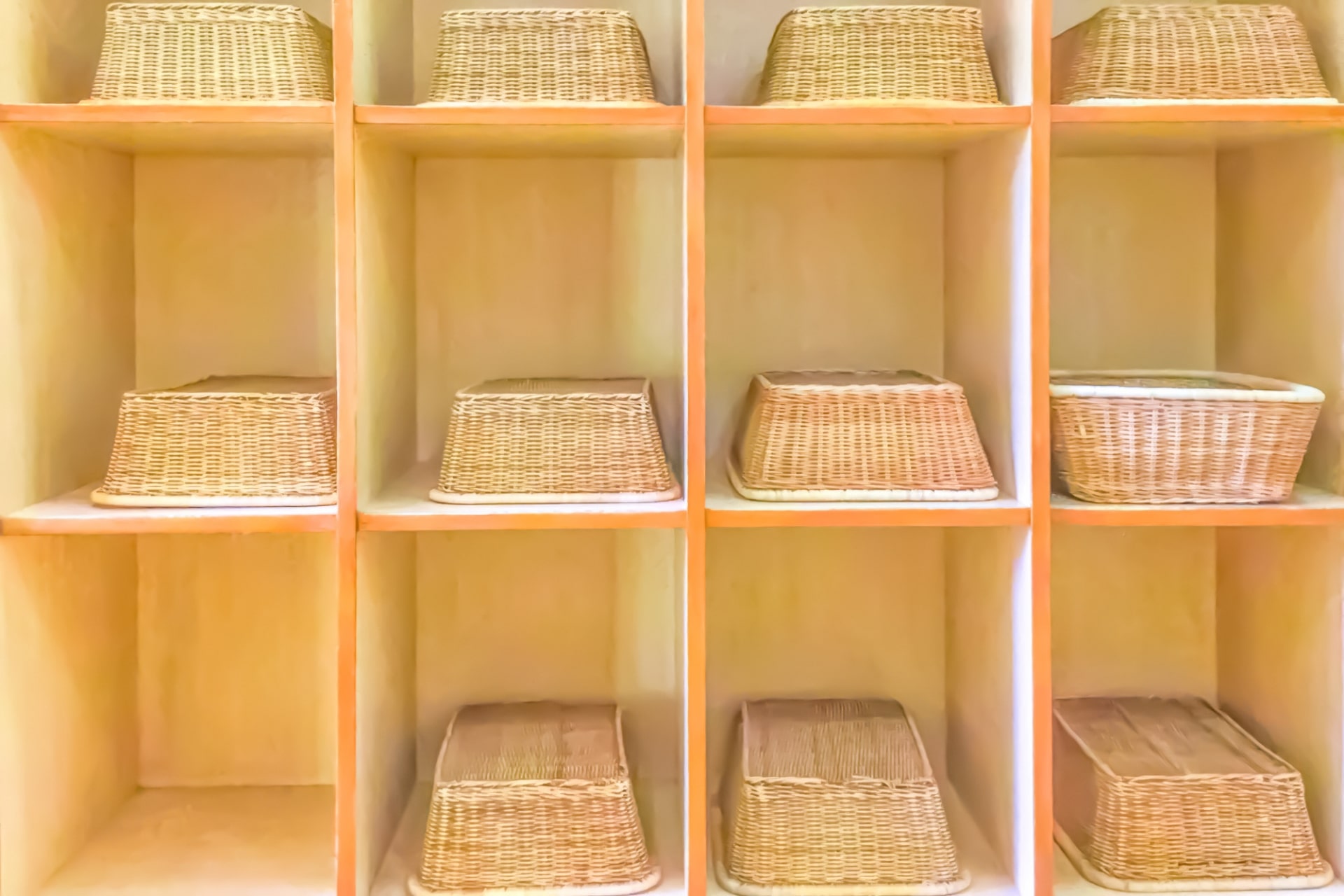

At the entrance, you’ll find a small area to remove your shoes and either a ticket machine or a reception desk for payment. From there, visitors proceed to gender-segregated changing rooms where lockers or baskets are provided for clothes and belongings.

The bathing area typically features a row of low stools and faucets and showers where you’ll wash and rinse thoroughly before entering the communal baths. These baths vary in size and design depending on the place, with different degrees of luxury and features. Many traditional sento also display hand-painted murals. Mount Fuji is a popular motif but many other designs can be found as well.

Amenities vary, but modern sento generally include saunas or relaxation spaces or massage chairs besides the bathing area.

How to Use a Sento: A Step-by-Step Guide

For first-timers, visiting a sento can feel unfamiliar, but the process is simple if you follow these steps:

1. Entering and Paying

Remove your shoes at the entrance and place them in a designated locker or shelf. Pay the entrance fee at the front desk or via a ticket machine. Fees are usually inexpensive in the case of local sento, ranging from 400 to 600 yen. Spa or Super Sento will generally cost at least twice that price.

2. Preparing in the Changing Room

Head to the gender-segregated area (typically marked with a blue curtain and the kanji (男) for men and a red one with the kanji (女) for women). Undress completely as bathing suits are not allowed. Store your clothes and belongings in a locker or basket. Bring a small towel for washing and a larger one to dry off later.

3. Washing Before Bathing

At the washing stations, sit on a stool and thoroughly clean yourself using soap, shampoo, and water from the faucets or showers. Rinse well, no soap should enter the communal baths.

4. Entering the Bath

Step into the communal bath slowly, and avoid splashing or disturbing others. Relax and enjoy the warm water, but be mindful not to put your small towel into the bath. You may keep it close to you or wrap your head with it.

5. Post-Bathing Rituals

When you’re finished, dry off with your towel before returning to the changing room. Many sento have areas where you can relax, enjoy a drink, or chat with friends before heading out.

Sento Etiquette: Do’s and Don’ts

Proper etiquette is key to enjoying a sento and ensuring everyone has a pleasant experience. Here’s a quick guide to what you should and shouldn’t do during your visit:

Do:

- Wash thoroughly before entering the bath. Cleanliness is essential; make sure to scrub and rinse yourself completely at the washing station.

- Keep your voice low. Sento are places of relaxation, so maintain a calm and quiet atmosphere even when chatting with friends.

- Bring your own toiletries. Most sento offer soap and shampoo, but you’re free to bring your own products. You’ll often see users with their own small basket entering or leaving the sento premises for this reason.

- Be mindful of your towel. Use a small towel to wash but never let it touch the water in the communal baths. Place it on your head or beside the bath instead.

Don’t:

- Splash or swim in the baths. The baths are for soaking, not playing.

- Use mobile phones. Phones in the bathing area are strictly forbidden for obvious reasons.

- Leave soap or other products around the washing area. Always rinse your station and leave it clean for the next person.

About Tattoos:

Most local neighborhood sento, considered a public service, do not discriminate against tattoos, unlike onsen where it’s usually forbidden, with few exceptions. However, super sento or spa-oriented facilities may request that tattoos be covered. Always check policies in advance if you’re visiting a larger bathhouse.

Why Visit a Sento?

Visiting a sento is an opportunity to discover another side of everyday Japan. For locals, sento have long been a place to relax, catch up with neighbors, and escape the stresses of daily life. For visitors, they provide a window into this communal culture while offering a moment of peace amid the hustle of travel.

Sento are also highly accessible, with many located in urban areas and costing only a few hundred yen. Unlike onsen, which often require travel to specific regions, sento are an affordable and convenient way to experience Japan’s bathing culture right in the heart of cities like Tokyo, Osaka, or Kyoto.

There’s something about the quiet charm of a neighborhood sento or the retro ambiance of a bathhouse with a Mount Fuji mural that feels authentic and quite unique. For many, including myself, despite having a proper bath at home, our local sento is a cherished place to unwind at the end of the day.

▽Subscribe to our free news magazine!▽

For more information about traveling in Japan, check these articles below, too!

▽Related Articles▽

▼Editor’s Picks▼

Written by

Photographer, journalist, and avid urban cyclist, making sense of Japan since 2017. I was born in Caracas and lived for 14 years in Barcelona before moving to Tokyo. Currently working towards my goal of visiting every prefecture in Japan, I hope to share with readers the everlasting joy of discovery and the neverending urge to keep exploring.