What’s the Difference Between Shrines and Temples in Japan?

Shrine vs Temple: Learn How to Identify Shinto Shrines and Buddhist Temples Through Beliefs, Architecture, and Rituals

Japan’s sacred sites come in two main flavors: Shinto shrines (神社, jinja) and Buddhist temples (お寺, otera). Shrines are built for Shinto, Japan’s indigenous animistic faith that reveres kami (gods or spirits in nature), while temples are for Buddhism, the religion introduced from China and India (through Korea) in the 6th century.

There are approximately 80,000 shrines and 75,000 temples located throughout Japan. These important historical sites are immensely treasured all over the country, serving as popular tourist attractions for both domestic and international travelers.

In practice, the Japanese often honor both traditions, but there are some clear elements that differentiate them both. Do you know the difference between a shrine and a temple?In this article, we will introduce the main clues to look for regarding beliefs, appearance, and worship practices, as well as recommend some must-visit sites.

Naming Conventions in Shrines and Temples

For starters, the name itself is one of the easiest ways to tell one from another. In general, Shinto shrines typically feature the characters 神社 (read as –jinja), 宮 (read as –miya or –gu) or 神宮 (read as –jingu, for high-ranking shrines), whereas Buddhist temples tend to end with the characters 寺 (read as –ji or –tera/dera) or 院 (read as –in). Some examples:

Meiji Shrine (Meiji Jingu 明治神宮), Namba Yasaka Shrine (Namba Yasaka Jinja 難波八阪神社), Kiyomizu Temple (清水寺 Kiyomizudera), Kinkakuji Temple (金閣寺Kinkakuji).

So even if you don’t know how to identify other traits, the name alone will be enough to know what each place is roughly about.

Shinto and Buddhism: Beliefs and Ceremonies

Shinto emphasizes harmony with nature and the blessings of life forces. So Japanese people believe that souls and spirits reside in Shinrabansho (everything in the universe); therefore, many worship mountains, forests, rocks, trees, and all other elements of nature as deities. Accordingly, Shinto rites tend to celebrate worldly events such as fertility, prosperity, and life in general. For instance, shrines host festivals and ceremonies for happy milestones: births, the 3‑5‑7 children’s rite (shichi-go-san), coming-of-age, and especially weddings, seeking the blessings of kami, or divine beings.

On the other hand, Buddhism emphasizes enlightenment and relief from suffering, so Buddhist rites often address death and the beyond. This is why temples are associated with funerals, memorial services, and prayers for ancestors. The Buddhist pantheon also encompasses a wide range of deities, enlightened figures, and guardians, so we can also find sites dedicated to figures other than Buddha.

This division of roles reflects the belief that kami confer everyday blessings, while Buddhist deities can guide the soul after death. In daily life, many Japanese visit shrines for New Year’s prayers or good-luck charms, and visit temples for incense and osenko offerings to Buddha, but the two practices often intermingle in the modern religious landscape.

Architectural Clues: Gateways, Guardians, and Buildings

Although these differences may not always be so clear-cut for reasons we’ll explain later, you can easily identify whether a site is a Shinto shrine or a Buddhist temple by paying attention to several basic structural details:

Gates, the Boundary Between the Mundane and the Sacred

A Shinto shrine’s path always begins under a torii (鳥居), a simple gate that symbolizes the boundary to holy ground. It’s often made of wood and painted vermilion, but we can also find them made of other materials such as stone, metal or reinforced concrete. A Buddhist temple, by contrast, may have a more elaborate mon (門) gate, sometimes with a heavy roof. Guardian statues usually flank these gates, whereas torii are unguarded arches.

Statues of Sacred Guardians

Look closely at the statues: shrines place a pair of mythical lion-dogs called komainu (狛犬) at the entrance to ward off evil. In the case of Inari shrines, we will find white foxes (Inari’s sacred messengers) instead. Temples may display Nio (仁王) guardians, fierce muscular figures on either side of the gate. For both komainu and Nio, one usually has the mouth open, and the other one closed, together representing the pronunciation of om or aum, related to the divine and the infinite.

Main Halls

Inside, a shrine complex is generally built of unfinished wood with minimal decoration. Its innermost sanctuary, called honden (本殿), is closed to the public and holds a sacred symbol of the kami (often a mirror, sword, or statue). In front of it is the worship hall, called haiden (拝殿), where visitors pray and make offerings. A temple compound, however, has a main hall, kondo (金堂) or hondo (本堂), devoted to a Buddha or Buddhist deity image and is open to worshippers. Temples also often include separate lecture halls, pagodas, and monks’ quarters.

Pagodas, Sacred Ropes and Other Ornaments

Multi-story pagodas (derived from the Indian stupa) are common temple structures, usually ornate and painted. Shrines rarely have pagodas (an exception is Itsukushima Shrine’s 5-story pagoda). Temples may also feature bell towers, incense burners, formal gardens, or cemeteries due to their close link to the afterlife.

Shrines usually feature a Shimenawa (注連縄), a sacred rope made of hemp or rice straw, woven in varying degrees of thickness, often accented with pieces of folded white paper, and frequently placed in front of the worship hall, although we can also find them tied around trees or rocks or near sacred waterfalls. In all cases, these act as protective barriers.

For purification purposes, all shrines have a temizuya (手水舎), a small pavilion with a water basin for ritual purification. Shrines also tend to emphasize natural simplicity, so there may be surrounding sacred forests or waterfalls.

Syncretism of Kami and Buddhas

However, for those of you who may have experience visiting some major shrines or temples in Japan, you have probably noticed that in some cases, these differences are not so clearly laid out. Maybe you have seen pagodas next to shrine premises, or torii gates within or right beside temples.

Historically, the line between shrine and temple was blurrier. For over a millennium, Japanese shinbutsu-shugo (神仏習合, “combining kami and buddhas”) meant that Buddhism and Shinto were deeply blended. From the Nara and Heian eras onward, a Buddhist temple would often be built next to (or even above) a local shrine, forming a jingu-ji (神宮寺) or shrine-temple. Kami were seen as Buddha incarnations (and vice versa); for example, in the Heian period, Shinto deities were interpreted as embodiments of Buddhist figures.

Famous sites once combined both: Usa Jingu in Oita Prefecture added a Buddhist temple (Miroku-ji) in 779, making it one of Japan’s first jingu-ji. Similarly, many mountain temples enshrined local kami as guardian deities. In these syncretic complexes, one could bow before a torii, then enter a pagoda or chant sutras in the same precinct.

Meiji-era Separation

All this changed abruptly in 1868. With the Meiji Restoration, the new government enacted the shinbutsu bunri (神仏判然令, “Kami and Buddhas Separation Order”), forcing a strict divide between Shinto and Buddhism. The goal was to establish State Shinto and diminish Buddhist influence. In practice, this led to the haibutsu kishaku (“abolish Buddhism”) movement: upwards of 30,000 Buddhist structures were destroyed or stripped of ritual objects. Many shrine-temples were dismantled. For example, Kamakura’s Tsurugaoka Hachimangu was forced to tear down its temple buildings and sell off its Buddhist statues (even the giant Nio guardians were relocated). After these reforms, surviving sites were clearly labeled: if it had been a shrine-temple, the shrine part remained and the temple part was lost (or vice versa). This separation is why modern shrines and temples look more distinct. Shinto shrines were refocused on kami worship alone, and Buddhist temples on Buddha worship alone.

Legacy of Syncretism in Shrines and Temples

Because of the long era of syncretism, visitors will still sometimes spot “mixed” features. Some notable examples include:

- The grounds of the famous Itsukushima Shrine in Miyajima include a five-story pagoda, a typically Buddhist form.

- Ryoanji in Kyoto has a small Shinto shrine dedicated to goddess Benzaiten (an example herself of a syncretic deity, with origins in East Asia Buddhism and adopted by Shinto) with its own torii in its precincts.

- Shitennoji Temple in Osaka has a prominent stone torii at the entrance.

- Many major shrines (like Hie or Kasuga Taisha) historically had Buddhist halls or images, and some still show Buddhist ornamentation in their oldest architecture.

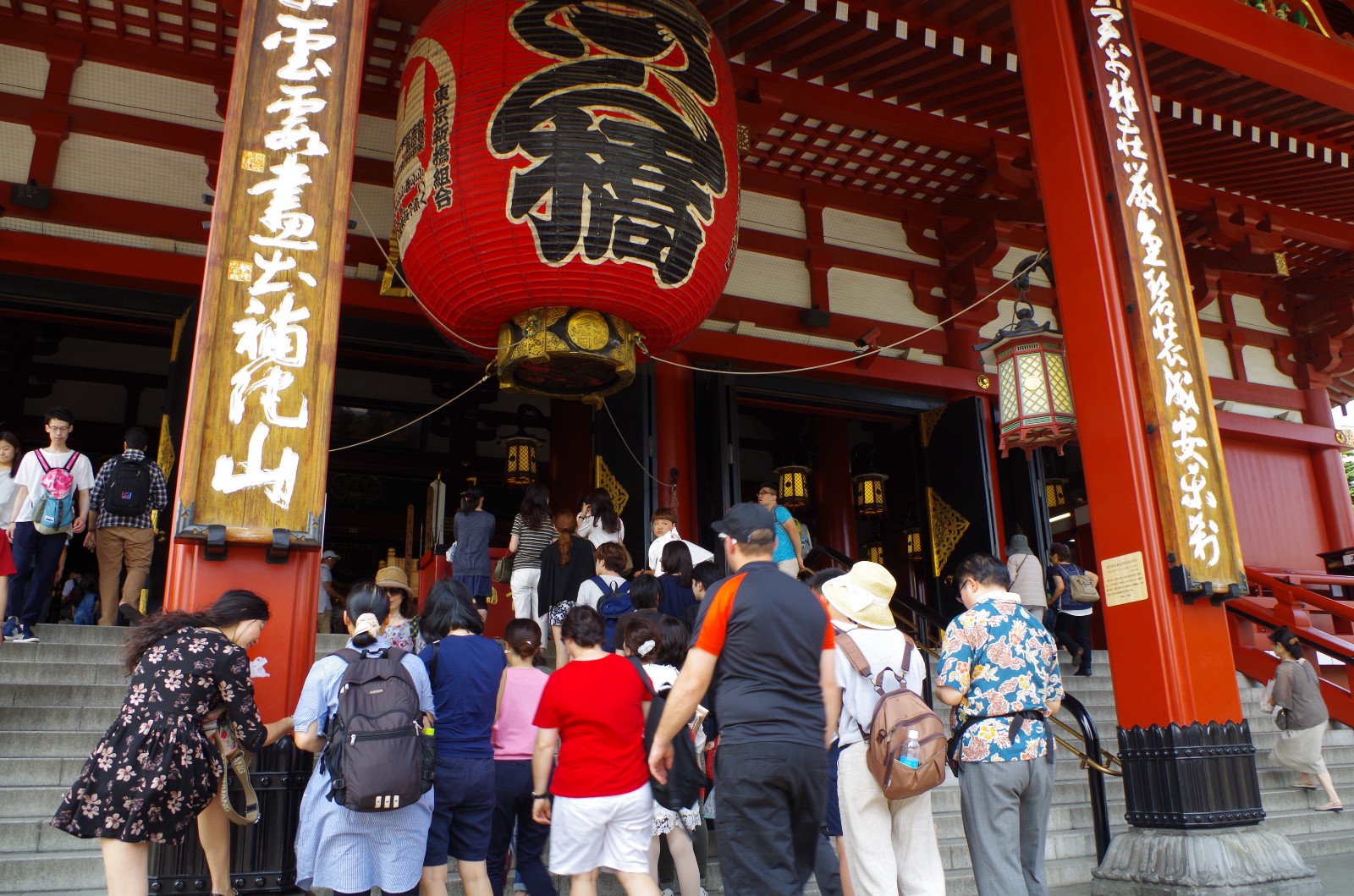

- Sensoji, Tokyo’s most prominent Buddhist Temple, features in its famous Kaminarimon Gate the Shinto gods Fujin and Raijin, deities of wind and thunder, respectively, hence the name. The reverse of the gate features the Buddhist dragon gods Tenryu and Kinryu, Heavenly Dragon and Golden Dragon, respectively.

- As you approach the grounds of Nikko Toshogu, there’s a prominent five-story pagoda, and then the Omotemon Gate features two Nio guardians (which were actually relocated to Rinnoji when Meiji enacted the separation order, but returned to their place in 1897).

Worship Manners

When visiting shrines or temples in Japan, it’s important to understand that the worship practices at each location differ slightly. Even some Japanese people may mix them up and use the methods from a shrine when they visit a temple. However, there are some common elements, with the most significant and frequent gesture being Ojigi, which means “bow down.”

Here’s a clear guide on how to worship at both places:

Temple Worship:

1. Bow your head just before entering the temple gate.

2. Walk along the side of the pathway after passing through the gate.

3. Wash your hands and mouth as follows: First, use the scoop to wash your left hand, then your right hand, and finally rinse your mouth. After rinsing, wash the handle of the scoop with the remaining water.

4. Touch the incense smoke. It is believed that the smoke has healing properties, so draw it toward any part of your body that is injured or unwell by waving your hand over it.

5. Pray. If there is a line, stand in line and wait for your turn. When it’s your turn, bow, throw money (any amount is acceptable*) into the offertory box, and then pray in silence with your hands clasped.

Shrine Worship:

Worshipping at a shrine is similar, but there are some specific differences in the prayer part. Follow these steps:

1. Make a bow and then throw money (again, any amount is fine*) into the offertory box.

2. Bow twice.

3. Clap your hands softly twice.

4. Make a final deep bow.

By following these guidelines, you’ll be able to respectfully engage in worship at both shrines and temples.

(*) There are no rules regarding how much you should offer at shrines or temples in Japan. However, 5 yen coins are a popular choice among Japanese visitors. This is because the word for 5 yen in Japanese is pronounced “goen,” which sounds similar to the words for fate, chance, or relationship. As the Japanese are quite fond of wordplay, it is common to see people making offerings of 5 yen or multiples of 5 (as in, multiplying their chances), such as 25 or 50 yen.

Japan is home to approximately 150,000 shrines and temples, so you may be wondering where to start. Now that you have a clearer understanding of how to identify each location, let’s discuss some recommendations to help you get started!

Check the article below to see the shrines that you cannot miss:

As for temples, these are the best spots:

If you’re looking for some photogenic recommendations in Tokyo, we got you covered:

In Japan today, shrines and temples coexist peacefully, each fulfilling its traditional role. This religious duality offers a captivating insight into the spiritual depth of Japanese culture, where ancient traditions are intertwined rather than kept apart. Understanding the historical blending and subsequent separation of Shinto and Buddhism sheds light on the shared characteristics and occasional surprises found at these sacred sites.

For more recommendations about shrines, temples or sacred sites, check the articles below!

Written by

Photographer, journalist, and avid urban cyclist, making sense of Japan since 2017. I was born in Caracas and lived for 14 years in Barcelona before moving to Tokyo. Currently working towards my goal of visiting every prefecture in Japan, I hope to share with readers the everlasting joy of discovery and the neverending urge to keep exploring.