Kita-Kamakura Temple Guide

How to Explore Kita-Kamakura: Top Temples and Walking Itineraries

Kita-Kamakura is a quiet counterpoint to the busier streets around Tsurugaoka Hachimangu, yet it holds the roots of what shaped Kamakura into one of Japan’s key centers of Zen thought. When the Kamakura shogunate rose to power in the late 12th century, the warrior class needed places for study, diplomacy, and spiritual discipline. Zen arrived from China at precisely the right moment, bringing practices that appealed to a government built on military order. Temples spread quickly along the northern valley, protected by hills that once served as natural defenses for the medieval capital.

Centuries of conflict, political intrigue, and the support of powerful clans have left behind an unusually dense concentration of monasteries. Some became major training hubs, while others turned into family temples or sanctuaries backed by influential patrons. It’s a place I’ve loved to explore over the years because it’s not as touristy and still carries traces of that world: quiet lanes leading to old sub-temples, long approaches lined with moss-covered stonework, and a rhythm of daily life shaped by active monasteries. Kita-Kamakura’s small stations and gentle slopes make it easy to explore, but its history remains anchored in the era when Zen shaped the minds and routines of the ruling elite.

If you’re like me and have a deep appreciation for history and traditional architecture, the following is an overview of some of the most important temples that I have visited during long walks, several times throughout the past decade, and that you shouldn’t miss if you have the opportunity to explore the northern hills of Kamakura.

The Most Important Temples of the Kita-Kamakura Area

Engakuji: A Grand Gate Into Kamakura’s Zen World

Engakuji (円覚寺) took shape in 1282, commissioned by Hojo Tokimune after the Mongol invasion campaigns. The idea was twofold: honor the fallen and create a serious center for Rinzai Zen just steps from the shogunate’s political core. Tokimune invited the Chinese Zen master Mugaku Sogen, who became the first abbot and helped define the temple’s character as a disciplined, international-facing monastery.

The complex was built along a long, rising valley that naturally encourages contemplation as you ascend. For centuries, Engakuji remained one of the most influential Zen temples in the region, producing monks, thinkers, and scholars whose work shaped Kamakura’s identity as a warrior capital with strong philosophical underpinnings.

What to See and Do at Engakuji

Your visit begins the moment you pass through the large Sanmon (三門) gate, an imposing wooden structure that frames the entire compound ahead, as the gateway to eliminating earthly desires. Behind it, the path runs straight through the core halls: the Butsuden (仏殿), where the main Buddha is enshrined, and the various buildings that form the complex, where meditation, training, or important ceremonies take place, like the Hojo (大方丈), originally the chief priest’s residence, nowadays a hall dedicated to various services and ceremonies. It can be visited freely, and it has a beautiful garden behind the building.

Engakuji is very much alive as a training monastery. This gives the complex a calm rhythm: monks moving between buildings, bells marking the hours, and occasional restrictions around practice halls.

Other Cultural Highlights

- Ogane (洪鐘) & Bentendo (弁天堂): Cast in 1301, this great bell is one of the signature bells of the Kanto region. Local legend says the bell has the protection of Enoshima Benzaiten, so there’s also a small shrine dedicated to this goddess, above a stairway lined with beautiful hydrangeas in Summer. And next to it, a small cafe with a nice terrace. This location’s vantage point gives you a moment to pause, look back over the rooftops, and appreciate the scale of the temple.

- Sub-temples and wooded paths: Branching routes lead to small sub-temples and shaded corners that many visitors skip. These areas reward slow exploration — mossy stonework, quiet garden pockets, and sudden views make the detours worthwhile.

- Grave of Yasujiro Ozu: If you’re an Ozu film enthusiast, you should know that his final resting place is here. It’s not difficult to locate his tomb, as it’s usually filled with offerings.

Visiting Tips

Engakuji opens early, and I find that mornings are the most rewarding time to visit, before most visitors arrive. It’s one of the first places I usually visit since it’s quite close to the train station. Light filters through the valley in a way that draws out textures in the old wood. Crowds gather especially in late November, when the maple trees around the main approach turn vivid, but quieter experiences are easy to find by wandering off the central axis.

The temple hosts zazen sessions for both beginners and experienced visitors, usually on weekends or early mornings (always confirm in advance in case you’re interested just in case). Even if you don’t join, it’s good to know that the temple’s purpose is still active, and your visit fits into a routine that has carried on for centuries.

Access Access |

1-min walk from Kita-Kamakura Station |

|---|---|

Business Hours Business Hours |

8:30 AM–4 PM |

Price Price |

500 yen |

Official Website Official Website |

http://www.engakuji.or.jp/ |

Tokeiji: A Sanctuary of Resilience with a Deeper Purpose

Tokeiji (東慶寺) was founded in 1285 by Kakusan-ni, widow of the regent Hojo Tokimune, making it a unique institution in a strictly patriarchal era. One of the things that surprised me the most the first time I visited was finding out that for nearly 600 years, it operated as a refuge for women who had nowhere else to turn: wives escaping abusive marriages could take shelter here, and after a prescribed period — historically around two or three years — they were legally granted a divorce. Note that during the Edo period, women still had many choices available for divorce, and this temple was considered as a last resort in cases of dire circumstances.

This role earned it nicknames like Kakekomi-dera (駆け込み寺, “run-in temple”) or Enkiri-dera (縁切り寺, “cut-the-ties temple”). Even during the Edo period, the temple held an extraterritorial legal status under the Bakufu. After the Meiji Restoration, in 1871, its power to grant divorces was abolished as divorce procedures became part of updated civil codes, and by 1902, it ceased functioning as a nunnery. Men took over, and it became a Rinzai temple under the Engakuji school.

Over its long life, many influential figures connected to Tokeiji: Emperor Go-Daigo’s daughter Yodo-ni once served as the abbess, and in more modern times, D. T. Suzuki, the Zen philosopher, contributed to its revival.

What to See and Do at Tokeiji

As you walk up the pine-lined stone steps to the thatched Sanmon gate (山門), you’ll immediately feel the quiet dignity that has defined Tokeiji. The temple is sometimes called a “temple of flowers”: plum blossoms in early spring, hydrangeas in early summer, Japanese iris and lush shade in the warmer months, and autumn leaves later in the year. Particularly during hydrangea season (late May–mid June), the paths are lined with a variety of hydrangeas, creating a very calm, almost secret garden feel.

For a more introspective experience, the temple offers daily sutra‐copying sessions (shakyo) in the morning for an extra fee. There are also zazen meditation sessions (often on Sundays) but only for those seriously interested in Zen, rather than casual tourist visitors.

Note: As of June 2022, photography became prohibited in many areas of the temple due to disrespectful visitors. So mind your surroundings and avoid taking out cameras or cameraphones in areas meant for prayer. The photos in this article were taken before this restriction took place.

Architecture & Artifacts

- The Main Hall (本堂), rebuilt in 1935 after the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake, reflects classic Zen architecture.

- There’s a small Bell Tower (鐘楼), with a bronze bell cast in 1350, that’s an Important Cultural Property of Kanagawa Prefecture.

- In the Matsuoka Hozo (松岡宝蔵) Treasure Hall, you’ll find temple treasures, including traditional lacquerware and other culturally significant objects.

Visiting Tips

During hydrangea season (late May–mid June), the paths are lined with a variety of hydrangeas, creating a very calm, almost secret garden feel. If you visit during this season, aim for a rainy morning as the petals deepen in tone and create a richer feeling under overcast skies.

The cemetery behind the temple is full of notable figures like monks, thinkers, and cultural personalities, as well as previous head priests. It may sound strange to recommend this place for a stroll, but it’s a spot I cherish because it’s usually quiet and filled with an eerie beauty. The grounds are lush and mossy, particularly gorgeous during summer, allowing for a reflective walk as you wander around the surroundings.

Access Access |

3-min walk from Kita-Kamakura Station |

|---|---|

Business Hours Business Hours |

9 AM–4 PM |

Price Price |

Free |

Official Website Official Website |

http://www.tokeiji.com/ |

Meigetsuin: The Blue Temple and Its “Window of Enlightenment”

Meigetsuin (明月院) started as a modest hermitage in the late Heian era (the first foundation is traced to 1159) and later developed into a prominent Zen sub-temple under the influence of regional power players like the Uesugi clan. The site we see today survived waves of institutional change: it outlasted the larger Zen complex it once belonged to and kept its distinct profile as a quiet, well-crafted garden temple.

This background explains the temple’s personality: compact but precise. There’s an architectural economy to Meigetsuin devoid of excess, with every path and planting feeling carefully composed to reward a short, focused visit rather than a long circuit. That economy is exactly why the circular window in the main hall became a signature image: it frames the garden like a single, curated photograph.

What to See and Do at Meigetsuin

Meigetsuin is so famous across Japan for its hydrangeas that it’s also commonly nicknamed Ajisaidera (Hydrangea Temple). In June the temple’s slopes are said to glow in “Meigetsuin blue” as several thousand plants bloom in shades from pale sky to deep indigo. It’s also why June mornings bring lines and a certain polite chaos. If you want the flowers without shoulder-to-shoulder crowds, I usually try to aim for the earliest opening time on a weekday or after a light rain (the colors deepen and the crowds thin).

The aforementioned circular window in the main hall facing the inner garden, often called the Satori Window (悟りの窓) or Window of Enlightenment, is a design device with a simple, potent job: turn the garden into a single, meditative image. Think of this also as a Zen lesson in composition. Visitors naturally line up for a photograph, but the best moment is quietly sitting, watching seasonal shifts: irises in spring, hydrangeas in June, green through summer, and a compact burst of autumn color.

Other interesting features include the Kaizando (開山堂), dedicated to the founder of the temple, and a cute jizo statue holding flowers that change with the season next to it.

Visiting Tips

Avoid weekends if possible during peak season, otherwise be ready for crowds depending on the time of the day. And if you decide to visit outside the peak season, you have my word that the temple is still pretty to look at during any other season. The Hondogo Garden (本堂後庭園) or inner garden closes about 1h earlier than the temple, so keep this in mind if you want to visit it as well.

Access Access |

10-min walk from Kita-KLamakura Station |

|---|---|

Business Hours Business Hours |

9 AM–4 PM |

Price Price |

500 yen |

Official Website Official Website |

https://trip-kamakura.com/place/230.html |

Kenchoji: The Grand Mother of Zen in Kamakura

Kenchoji (建長寺) is arguably the Zen institution that helped define samurai spirituality in early Kamakura. Founded in 1253 by Hojo Tokiyori, with the Chinese Zen master Rankei Doryu (Lanxi Daolong) as its first abbot, Kenchoji became a top-tier center for Rinzai training.

It ranked first among the Kamakura Gozan (the Five Great Zen Temples), giving it high religious and political status. For centuries, it was a working Zen monastery and a symbol of state power, as the Gozan system actually functioned like a proto-ministry for the shogunate, using temples to relay political norms across their networks.

Over time, Kenchoji faced disasters like earthquakes, fires, and successive rebuildings, but remained central. Its grounds stretch from deep in the valley all the way into forested hills, with sub-temples, hiking paths, and hidden viewpoints.

What to See and Do at Kenchoji

The Sanmon Gate (三門) is where your Kenchoji experience begins, a grand three-gate that marks the threshold into the sacred. Surrounded by trees as if I were in the middle of a thick forest, this is one of my favorite spots. Within the premises, you’ll find the Butsuden (仏殿) or the Buddha hall, where Jizo Bodhisattva, a bodhisattva of compassion, is enshrined. The image, built in 1628, belonged originally to Zojoji Temple in Tokyo but was donated to Kenchoji in 1647.

Continue walking further, and you’ll see the Karamon Gate (唐門), a gorgeous and richly decorated gate originally built in 1628, also in Tokyo’s Zojoji Temple as the mausoleum gate for the Shogun Hidetada’s wife, and then donated the same year as the bodhisattva.

Don’t miss the Hatto (法堂), which used to serve as a lecture hall. The building houses an interesting image of a Thousand-Armed Kannon (千手観音) and the painting of a powerful dragon among the clouds in its ceiling.

At the end of your visit, there’s Teien Garden (庭園), designed by temple founder Rankei Doryu. This tranquil garden and pond frames the pavilions that were used for receiving guests, and it’s a place where I like to just sit down for a few minutes and take in the simple beauty of the garden and its surroundings.

Access Access |

18-min walk from Kita-Kamakura Station |

|---|---|

Business Hours Business Hours |

8:30 AM–4:30 PM |

Price Price |

500 yen |

Official Website Official Website |

http://kenchoji.com/ |

Hansobo: A Protector on the Hillside

High above Kenchoji sits Hansobo (半僧坊), a somewhat unexpected but magical spot tucked into the temple’s mountain flank. Rather than a traditional Buddhist hall, Hansobo is a Shinto-style shrine dedicated to Hansobo Daigongen, a protective spirit brought to Kencho-ji in 1890 from Hokoji in Shizuoka. As the guardian deity of Kenchoji, Hansobo is particularly revered for fire protection. According to tradition, even during major disasters, people with talismans or images of Hansobo survived unscathed.

What makes Hansobo vivid in folklore, and the reason why it’s one of my personal favorites, is its association with tengu, the long-nosed, mischievous-yet-mighty creatures of Japanese legend. The shrine access is lined with 12 statues of karasu-tengu (crow tengu), guardians said to serve Hansobo.

What to See and Do at Hansobo

The Ascent is a little steep but undoubtedly a rewarding climb: about 250 stone steps wind up from Kenchoji to the shrine. As you approach the shrine, the tengu statues keep watch, and their stony faces feel both playful and solemn, reminding us this is a place of power and protection.

Once you reach Hansobo’s hilltop, there’s a viewing platform that opens out to breathtaking sights: on a clear day, you can see Sagami Bay, Kamakura, and even Mt. Fuji in the distance. For those willing to climb further (an additional ~180 steep steps), there’s an even higher lookout with a more rugged, less-touristy feel.

In autumn, the path is framed by vivid maple foliage, which intensifies the sense you’re entering a secluded high place. During early summer / rainy season (June–mid July), hydrangeas bloom along the ascent, adding bursts of color among the stone and moss.

Visiting Tips

From the upper gardens of Kenchoiji, follow the stone stairway. It’s clearly marked and part of Kenchoji’s general temple grounds. The climb takes around 10–15 minutes, depending on your pace. Hansobo is also the gateway to the Ten-en Hiking Course, a ridge trail that links Kencho-ji with other parts of Kamakura’s mountain paths.

The shrine has a special Omikuji inside an adorable karasu doll, so in addition to finding out about your fortune, it’s a cute and unique souvenir.

Access Access |

About 30-mins walk from Kita-Kamakura Station (via Kenchoji) |

|---|---|

Business Hours Business Hours |

8:30 AM–4:30 PM |

Price Price |

Free |

Official Website Official Website |

http://www.kenchoji.com/hannsoubou.html |

Extra Side Trip 1 – Houkokuji and the Bamboo Forest: A Samurai Family’s Retreat in Bamboo and Stone

Houkokuji (報国寺) isn’t technically part of the Kita-Kamakura area, but it’s outside of the usual Kamakura routes and a worthy inclusion in this guide because of its beautiful bamboo garden. It took shape in 1334, commissioned by Ashikaga Ietoki, the grandfather of Ashikaga Takauji, founder of the Muromachi shogunate. The temple’s origins are also tied to Shigekane Uesugi, retainer of the Ashikaga clan. And thus, the temple served as a bodaiji (family temple) for both the Ashikaga and Uesugi families, a place to honor ancestors and maintain the spiritual backbone of a clan about to rise from regional power to national rule.

As a temple belonging to the Kenchoji school of the Rinzai sect of Buddhism, Hokokuji is also strongly linked to Kenchoji. The temple’s later nickname, the “Bamboo Temple,” came long after its founding, when the beauty of its bamboo garden and its teahouse began attracting visitors. Its bamboo forest form a narrow, soaring grove that turns sound and light into the main attractions, along with the temple’s quiet tea house, where you can enjoy a relaxing cup of matcha while enjoying the scenery.

What to See and Do at Hokokuji

The temple’s main attraction is the bamboo, but there’s also a dry landscape garden next to the Main Hall with a beautiful scenery that represents mountains and rivers with different patterns on the sand. There are sections covered in moss, creating an interesting contrast that’s particularly pretty during summer when the green colors are at its most vibrant.

Around the surroundings, you’ll see some striking rock formations; these are yagura burial mounds with several graves, among them the one belonging to the temple’s founder, Ashikaga Ietoki. Walk the pebbled path through the grove and listen to the bamboo sounds in the breeze as you pass by stone lanterns and small Jizo statues, sitting like punctuation marks among the trunks.

Around 2,000 Moso bamboo stalks form the temple’s signature grove. The path curves slightly and encourages you to slow your pace. The grove wasn’t planted for show. It originally provided material for everyday temple use items like baskets, tools, fencing practice items, before becoming the atmospheric highlight that visitors now seek out.

At the back of the grove is Kyuko-an (休耕庵), a small teahouse (with an additional admission fee) where you can order matcha and a wagashi (sweets) while gazing into the bamboo.

Visitor Tips

Visit during early mornings on weekdays for low crowds; Hydrangea season (June) and late-November for autumn color are peak windows if you don’t mind company.

The temple hosts zazen sessions every Sunday starting at 7:30 until 9:15, open for anyone without requiring reservations. Check in at the main hall.

Access Access |

12-min bus from Kamakura Station |

|---|---|

Price Price |

400 yen (Additional 600 yen required for tea house) |

Official Website Official Website |

http://www.houkokuji.or.jp/ |

Extra Side Trip 2 – Ofuna Kannonji: The White Kannon Looking Over Kamakura

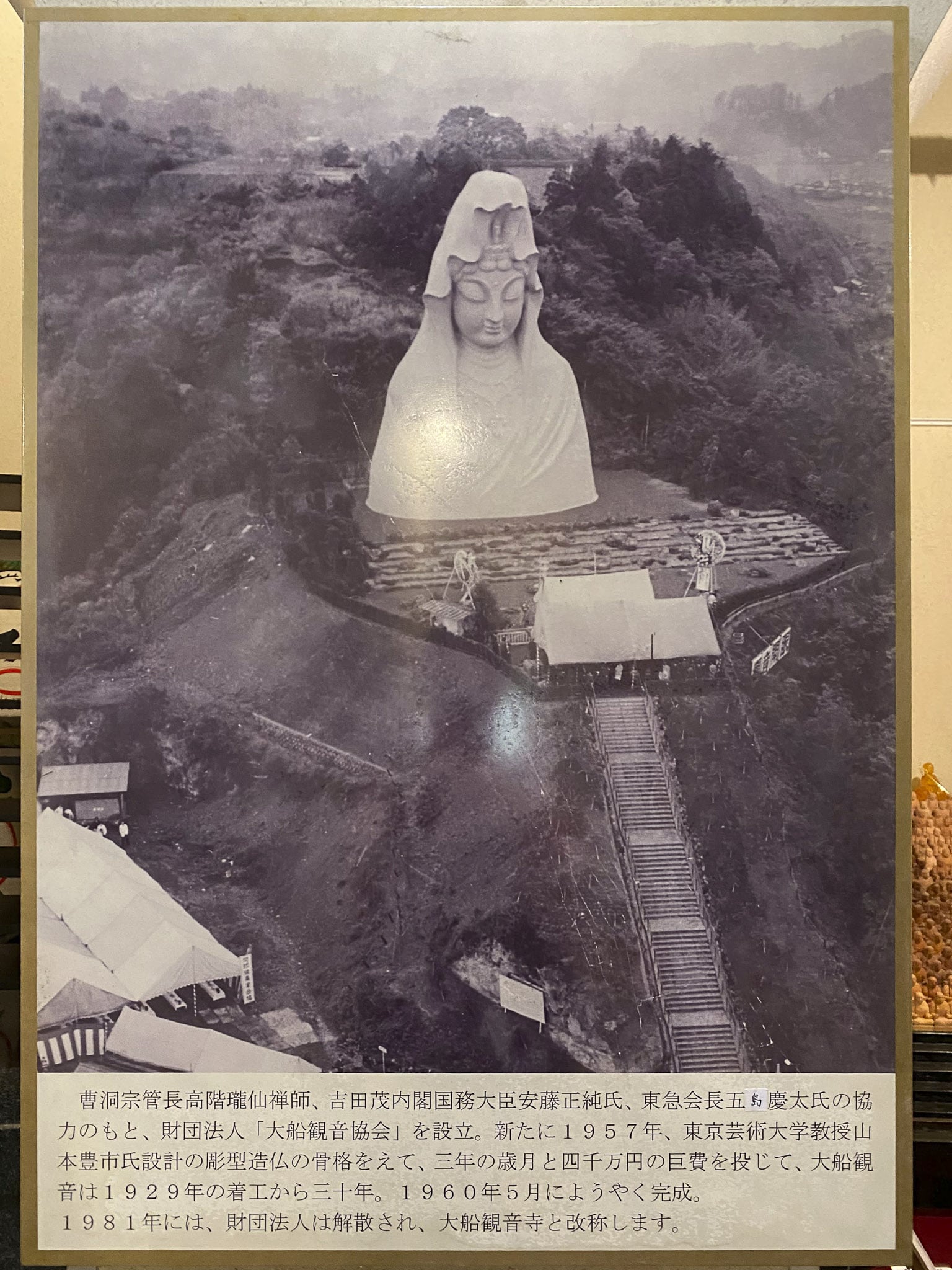

Contrasting the previous list of locations, Ofuna Kannonji (大船観音寺) isn’t a centuries-old Kamakura temple but a relatively recent addition to the local landscape, with its story beginning in the 20th century. In 1927, a group of citizens formed the Gokoku Ofuna Kannon Association to build a massive Kannon statue as a symbol of compassion and national healing after the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923.

Construction began in 1929 on a hill just west of Ofuna Station. The original plan was a standing Buddha-like figure, but ground instability forced a redesign: the statue eventually became a 25-meter-tall bust of the Byakue (white-robed) Kannon (白衣観世音菩薩像).

Work stalled in the 1930s because of the Great Depression and then WWII. The project resumed after the war, and the statue was finally completed in 1960, built entirely by hand using poured concrete. While the monument was originally motivated by a desire to protect and heal society, the construction revival after the war carried a powerful message: a commitment to mourn the war dead, promote reconciliation, and pray for a future without conflict.

In 1981, the temple was officially established under the Soto Zen school, affiliating with Daihonzan Sojiji.

What to See and Do at Ofuna Kannonji

The most eye-catching feature is the giant white-robed Kannon that dominates the hilltop. From a distance, it looks peaceful yet monumental. Up close, you can actually enter the statue. Inside, there are many small Buddha figures and a small exhibition space dedicated to peace, particularly remembering the atomic bomb victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (stones from those sites were embedded into the statue).

Temple Grounds & Features

- Sanmon (山門): Built in modern times, but positioned in the classic Zen style to mark the entrance.

- Shoshin-kaku Hall (照心閣): This is where the principal Kannon image is enshrined. The building is meant for reflection and meditation, named to reflect Buddhist introspection (“shining one’s heart”).

- Daibonsho Bell (大梵鐘): A large bell, donated by a prominent local figure, is rung daily.

- Matchmaking Tree: A tree on the grounds where visitors come to pray for relationships and family harmony.

- Jikodo Hall (慈光堂): A hall dedicated to love and compassion. The light from a special flame (or statue detail) is said to bring a kind of “light of love” to those who visit.

Visitor Tips

The temple is usually quiet in the afternoon so it’s suitable to stop by after exploring Kita-Kamakura before heading back to Tokyo. Evenings or special events when the statue is lit up are memorable as well.

If you are riding the monorail to/from Enoshima, pay attention when you’re close to Ofuna, as you’ll spot a nice view of the Kannon from afar. Also, the bridge from Ofuna Station allows for a nice general view.

Access Access |

5-min walk from Ofuna Kannonji Station |

|---|---|

Business Hours Business Hours |

9 AM–4 PM |

Price Price |

300 yen |

Official Website Official Website |

http://www.oofuna-kannon.or.jp/index.html |

Suggested Walking Routes Around Kita-Kamakura

Kita-Kamakura is compact, but each temple has its own rhythm and a different level of walking involved. The routes below follow natural geography and avoid pointless backtracking. They also build in realistic time estimates without listing rigid schedules. You can move faster or slower, but these outlines reflect how most people tend to explore the area.

Route A — Classic Kita-Kamakura Line-Up

Engakuji → Tokeiji → Meigetsuin → Kenchoji → Hansobo

This is the signature north-valley route. Start at Engakuji, which sits right at the station, then follow the gentle incline along the road to reach Tokeiji. From there, continue toward Meigetsuin, which usually draws the biggest crowds in June; outside hydrangea season, it’s still a comfortable stop with manageable flow.

After Meigetsuin, cross the tracks and walk toward Kenchoji. The shift is obvious the moment you step in: the scale jumps, the buildings get larger, and the grounds extend deeper into the hillside. If you still have energy, add the climb to Hansobo at the back of the precinct. The ascent isn’t long, but it’s steep enough to make you pay attention. The reward is a broad viewpoint and a set of guardian tengu statues that feel slightly surreal after the polished Zen architecture below.

This route works for a first visit and gives a good sense of how Rinzai Zen shaped the area.

Approximate total walking time (may vary depending on the time spent on each spot): around 60–75 minutes.

Route B — Kita-Kamakura to Eastern Kamakura Through Green Backroads

Kenchoji → Hansobo → Ten-en Hiking Trail → (optional) Zuisenji

This option is for people who don’t mind dirt paths and a bit of climbing. Start at Kenchoji, head straight to Hansobo, then continue past the shrine into the woods. You’ll join the Ten-en hiking trail, a ridge path that runs behind Kamakura’s main basin. It’s shaded, airy, and far enough from traffic that you can hear insects more than cars.

Eventually, the trail descends toward Zuisenji, which is not covered on this list but it’s a popular choice for those hiking this particular trail because of its picturesque gardens. Ending the walk here puts you in a quieter corner of eastern Kamakura after undertaking a bit more of a challenge, with easy access to buses heading back toward Kamakura Station.

Approximate total walking time (may vary depending on the time spent on each spot): 90–120 minutes, depending on pace.

Route C — Kita-Kamakura + Bamboo Finish

Engakuji → Tokeiji → Meigetsuin → Houkokuji

This route starts like the classic lineup but shifts east after Meigetsuin. From the temple, walk down toward Kamakura Station, cut through residential streets, and continue to Houkokuji. The road has a suburban feel, with low houses and small gardens replacing temple walls and stone gates. When you finally reach the bamboo grove, the contrast works in your favor: the sudden drop in light and sound makes the entrance to Houkokuji feel sharper.

The tea hut is a welcome break after covering the longer stretch from Kita-Kamakura. People often end the day here with matcha before catching a bus back to Kamakura.

Approximate total walking time (may vary depending on the time spent on each spot): 70–90 minutes.

Route D — Adding Ofuna Kannon as a Side Trip

Ofuna Kannon → Kita-Kamakura temples of your choice

Ofuna Kannon sits outside the usual Kita-Kamakura cluster, but it links cleanly with the rest of the area because Ofuna Station is only one stop away on the JR Yokosuka Line. The best way to include it is simple: you may either schedule it for the first or last visit, before or after Kita-Kamakura for whichever route you prefer. I did suggest above that afternoons are quiet, but perhaps if you’re coming from Tokyo, it’s just easier to stop first by Ofuna.

Start by climbing the short slope to Ofuna Kannonji. Going inside the massive Kannon changes your understanding of the site — the hall-like interior and peace memorial corner give it a very different tone from the older Zen temples. Once finished, return to the station, ride one stop, and begin either Route A, B, or C depending on your energy level.

Approximate walking time at Ofuna Kannon: very short, about 10–15 minutes from station to gate, plus however long you linger inside the statue.

Which Route to Choose?

- First-timers: Route A

- Hikers / people wanting views: Route B

- People who want a calm finish with tea: Route C

- People curious about the modern monument: Route D

Kita-Kamakura works best when you don’t rush it. The temples sit close together, but each one has its own personality: Engakuji’s open terraces, Tokeiji’s compact charm, Meigetsuin’s seasonal crowd magnetism, Kenchoji’s straight-line grandeur, Hansobo’s hillside quiet, and Houkokuji’s bamboo shade shaped by the Ashikaga clan. Add Ofuna Kannon as a modern counterpoint, and the area becomes an easy mix of history, architecture, and short walks that feel manageable in half a day or a full one if you stretch it.

The temples are active religious sites, but they’re also part of a landscape that people have been walking through for centuries. Visiting a handful of them gives you a good sense of how Zen first took root here and how these valleys shaped the character of Kamakura as a whole. The routes are flexible, so pick one that matches your pace and let the area unfold naturally.

For more information about the Kamakura area, check out the following articles!

Written by

Photographer, journalist, and avid urban cyclist, making sense of Japan since 2017. I was born in Caracas and lived for 14 years in Barcelona before moving to Tokyo. Currently working towards my goal of visiting every prefecture in Japan, I hope to share with readers the everlasting joy of discovery and the neverending urge to keep exploring.