Differences in Early Years Education between Japan and the U.S.

Early childhood education in Japan vs. America

Early years education in Japan is unique and interesting. Having experienced early education in the U.S. with one of my children and early education in Japan with another, I have noticed a lot of differences. This article will focus more on differences in philosophy and daily life rather than the administrative aspects. This article will also focus more on hoikuen, which is more the Japanese equivalent of American daycare.

An Overview: Hoikuen vs. Youchien

To understand how early childhood education is different in Japan compared to the U.S., let me give a brief overview of the system here in Japan. Early years education in Japan has two categories: Hoikuen or Youchien. Hoikuen is nursery school and falls into the purview of the Ministry of Healthy, Labour and Welfare. Babies aged 5 months old to kids aged 5 years old are eligible to intend, though it depends on the school. Criteria for entry, however, are based on the parents’ time and ability to provide childcare. Despite Japan’s low birth rate, there is a general undersupply of daycares, leading to a competitive application process. This is especially true for public hoikuens, which are government-funded and in some cases government-run. This also tends to be true in cities like Tokyo. If there are not enough spots for everyone, your family receives greater priority if both parents work and if you have already spent some time on the waiting list.

Youchien, on the other hand, falls into the purview of the Ministry of Education. Youchien is basically pre-kindergarten. Its purpose is geared more toward academic development than childcare. As such, it is generally not as difficult to secure a spot.

Is This Montessori?

All the different types of early education in Japan seem to have the common goal of nurturing independence in little ones. Babies are taught to eat by themselves using utensils from an early age. My daughter has been using training chopsticks at her school since she turned two. Teachers also encourage young toddlers to drink from an open cup rather than a no-spill sippy cup. Likewise, these little toddlers are taught to get dressed by themselves. My daughter takes her own shoes off when she arrives at school and puts them on again when she leaves.

Although this varies by school, our hoikuen is quite small and has a lot of mixed-age group play. I have also found that, instead of buying crafts supplies, schools have the kids make use of things like old newspapers. They will use it for origami, coloring, and costume-making. Now, you may be thinking that this sounds a bit like Montessori education. I think there are quite a few similarities between the Montessori method and the Japanese “method”, especially in terms of nurturing independence. The difference is that, in the U.S., Montessori is a specialized area of education, one often reserved for families with greater means. In Japan, this is a more generalized philosophy that has deep roots in the common Japanese culture.

Japanese early education also emphasizes nature to a huge extent. They take walks every day, weather permitting, and the kids are encouraged to truly engage and understand their surroundings outside by picking up leaves, asking questions, and observing animals and insects. This is perhaps unsurprisingly given the significant role that nature plays in Shintoism and Japanese culture. This is also one of my favorite things about early education here.

The Teachers: a Career for the Long Run

In the U.S., my kids attended a private neighborhood daycare. The teachers were warm, friendly, and caring, as was the environment. The kids enjoyed yoga, music lessons, story time, outdoor time, and more. They ate a reasonably well-balanced lunch by American standards. I was sad to leave. When we started hoikuen in Japan, however, I was blown away by the sheer professionalism of the hoikuen teachers, or hoikushi. These teachers seemingly pay more attention to my kids than I do and take note of details that even I would have missed. They have never lost anything, not even a stray hair tie.

Hoikushi (保育士) are trained for this very specific role, and it shows. To become a hoikushi, you must graduate from a vocational school for hoikushi authorized by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. You must have had more than 14 years of schooling, including from either a 2 year college or 4 year university. After this, you must pass a practical examination and a written examination, held twice a year. Reportedly, the passage rate is less than 50%. That is not to say that all hoikuen teachers are fully licensed in this way, but the general impression is that this is a long-time career for most. In contrast, there is a relatively high turnover rate for American daycare teachers, many of who are passing through the profession onto other pursuits. The pay, while definitely not high on either side of the ocean, is more livable for hoikushi, and the overall quality of the profession reflects that.

The Nitty Gritty of Parent Involvement

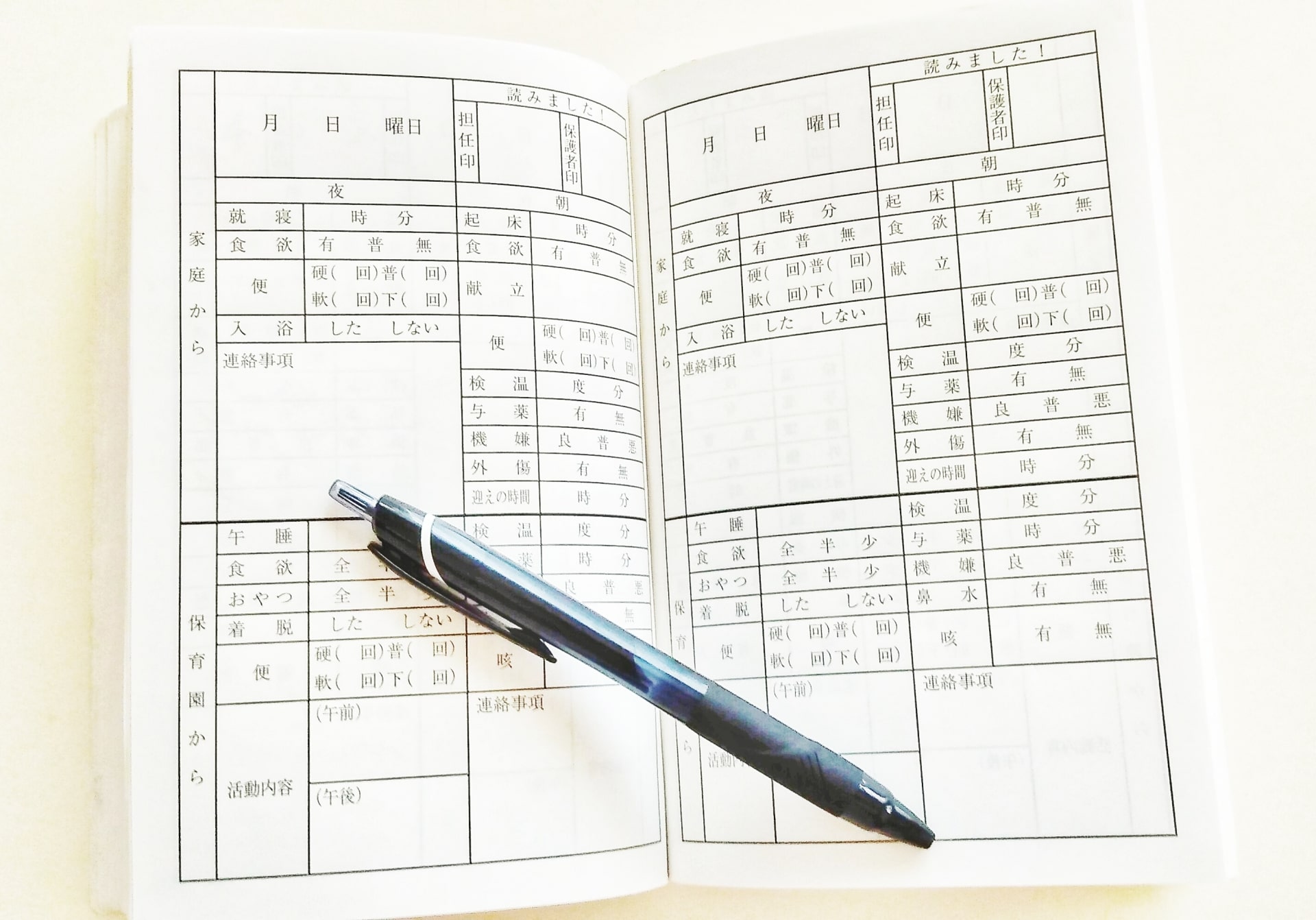

Remember I mentioned that hoikuen teachers are extremely detail-oriented? This is mostly great but comes at a cost. The cost is that more is demanded of the parents as well. In America, most daycares will use apps to inform you of nap times, meals, and irregular incidents. In paper-based Japan, teacher-parent communication centers on the renrakucho (連絡帳), literally the “communication notebook.” As a parent, I am expected to write in it everyday regarding what time my child woke up, when she went to the toilet (I’m even encouraged to detail the quality of her poop!), meals, temperature, current mood, etc. At the end of the day, the renrakucho is returned to me with much of the same information from during the day. It often has little anecdotes about funny things she said or did, which I love. The renrakucho, as much of a pain as it is, does make the experience more personal.

Much is demanded of parents in other ways too. In the U.S., I sent my kids off with a couple of sets of spare clothes, a hat, and some milk when they were infants. Here is a typical list of things parents must supply:

- Renrakucho

- Diapers & wipes (Some schools require parents to write the child’s name on each and every diaper! Luckily, our hoikuen supplies all diapers and wipes)

- An extra set of clothes, everyday (The kids change into a clean set of clothes after lunch, probably due to the mess the kids make feeding themselves)

- Two sets of extra clothes, including socks and underwear

- Yet another set of clothes for water play during the summer months

- An extra pair of shoes for walks (I still don’t quite understand why the kids can’t wear the shoes they arrive in)

- Food bib

- Blankets for naps

- Water bottle with a strap

- Hoikuen-issued hat

Then there is a list of rules, some of which might be surprising for non-Japanese parents. These include:

- No hair ties with accessories on them, no matter how small (choking hazard)

- No tiny hair ties (choking hazard)

- No accessories of any kind

- No dresses (it could get caught somewhere during play)

- No flouncy shirts that look like dresses (same reasoning as above)

- No coats or jackets with hoods (other kids might pull them, creating a choking hazard)

Well, there you have it! How does early education in Japan compare to that where you live? On the whole, it has been a positive experience and one that contrasts quite a bit with secondary and higher education in Japan. I hope you found this article interesting. If you would like to read more about life in Japan, check out the following articles for additional info!

Written by