10 Common Japanese Jokes (Oyaji Gyagu)

Or how to risk getting yeeted from your next Japanese gathering

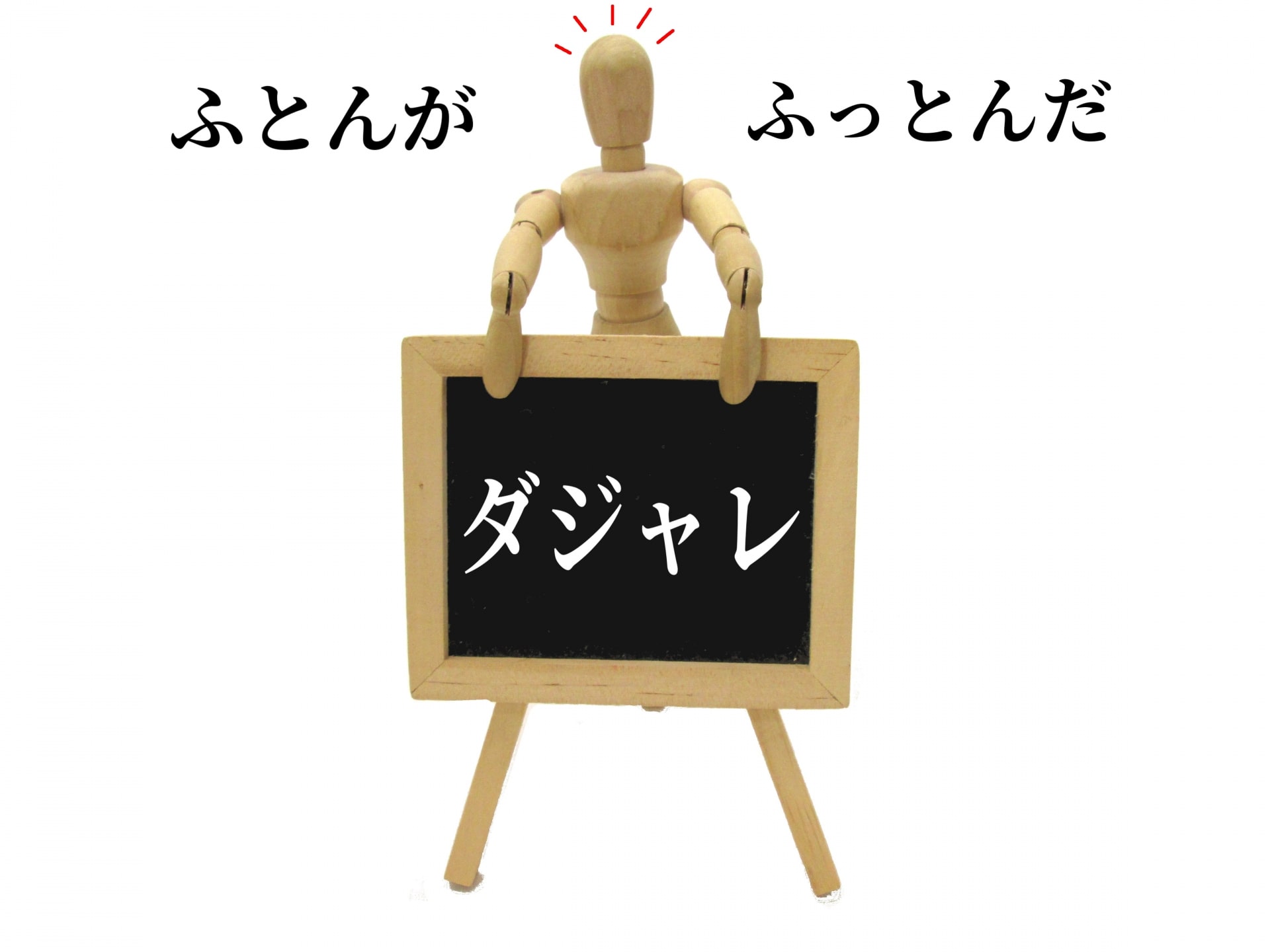

One of the most fascinating things about the Japanese language is the way it takes advantage of its insane number of homophones and its multiple kanji readings for the sake of creating an endless stream of puns, called dajare (ダジャレ). In skilled hands, it allows for multi-layered and complex wordplays that throughout history, have laid the foundations of Japanese poetry, literature, and sophisticated comedy.

But that’s not what we’re going to talk about today.

Today we’re discussing the lighter side of said puns, commonly known as oyaji gyagu (おやじギャグ), literally “old man gag” or “old man joke”, which as you may have guessed by now, is the Japanese equivalent to the infamous dad jokes.

What kind of jokes are the oyaji gyagu?

Part of the joy of silly wordplays relies on the “lame” factor to generate a degree of secondhand embarrassment in the audience. It needs to be unfunny but somewhat clever to get some (awkward) smiles but not too sophisticated, lest we land in the pro-comedy minefield. It’s about walking the tightrope between amusement and cringe just enough so you’re not expelled from future social gatherings.

And although puns in the Japanese language have quite old historical roots, it’s said that the current form of oyaji gyagu is originated in a popular song from the 70s, called The song of the fishmonger (魚屋のおっさんの唄), which also partly explains why these are known nowadays as old man jokes. However, despite the name, the appeal of these jokes is quite broad among the Japanese, regardless of age.

Types of Japanese dad jokes

Same sound, repeated twice

This is the most basic form of oyaji gyagu and probably the one you’ll hear more often. It basically consists of repeating two words with the same (or almost the same) sound but with different meanings, to get a somewhat coherent phrase. For example:

- Shouga nai, shouganai (生姜ない、しょうがない) [There’s no ginger, it can’t be helped.]

Shouga means “ginger”, and Shouganai is a very common phrase in situations where nothing else can be done.

- Ikura wa ikura? (いくらはいくら?) [How much is the salmon roe?]

Ikura means “salmon roe”, and also means “how much” with regards to the cost of something.

Phrasing with more than one meaning

Generally, with so many homophones lying around, proper meaning is obtained through context or via kanji (when in written form). But when it comes to making a joke, homophones are a good opportunity to get funny outcomes from seemingly innocuous phrases:

- Nee, chanto ofuro haitteru? (ねえ、ちゃんとお風呂に入ってるの?) [Hey, do you take a bath properly?]

- Neechan to ofuro haitteru? (ねえちゃんとお風呂に入ってるの?) [Are you taking a bath with your sister?]

Here, nee is used as an interjection, while chanto means “proper”, but the meaning quickly changes when combining both, as neechan means “sister”. In the following example, a very slight pronunciation change creates a radically different meaning:

- Pan tsukutta koto aru? (パン作ったつくことある?) [Have you ever made bread?]

- Pantsu kutta koto aru? (パンツ食ったくことある?) [Have you ever eaten underwear?]

Fun with English loanwords

Given the high percentage of loanwords from English, it’s obvious that many jokes would also involve the use of said loanwords, both for their meanings and their sounds. Like in the following phrases:

- Boushi wo wasurete hatto shita (帽子を忘れてハットした) [I forgot my hat and made a hut].

Here there’s an added gag since the loanword for “hut” also sounds very similar to “hat”.

- Toire ni ittoire (トイレに行っといれ) [Have a nice time in the toilet)

Toire is a loanword for toilet, and ittoire is an abbreviated form of itterasshai, which is commonly said to wish a good day to someone going somewhere else.

List of common Oyaji Gyagu

- Futon ga futtonda (布団が吹っ飛んだ) [The futon blew away]

- Neko ga nekonda (猫が寝込んだ) [The cat fell asleep]

- Arumi kan no ue ni aru mikan (アルミ缶の上にあるミカン) [The tangerine on top of the aluminum can]

- Asari wo assari to taberu (アサリをあっさりと食べる) [Eat clams lightly]

- Sukii wa suki (スキーは好き) [I like skiing]

- Naiyou ga naiyou (内容が無いよう) [There is no content/substance it seems]

- Iruka wa iru ka? (イルカはいるか?) [Are there dolphins?]

- Shika shika nai (鹿しかない) [There’s nothing but deers]

- Choko wo chokotto tabeta (チョコをちょこっと食べた) [I ate a bit of chocolate]

- Denwa ni daremo denwa (電話に誰も出んわ) [No one’s answering the phone]

How do you measure the success of your delivery? Ok, so we have established that rather than actually amusing our audience, these jokes are mostly meant to amuse ourselves at the expense of the poor audience’s annoyance.

If the usual answer to dad jokes are awkward looks and side eyes, the most typical response to bad jokes in Japanese is to say samui… which means “it’s cold”, or to make some shivering gestures to convey that the room suddenly became colder. Maybe some fake laughs here and there.

Language Learning With Pun-damental Japanese

Embracing Japanese dad jokes comes with the bonus of helping you get to grips with the Japanese language. You’ll get a better understanding of words with multiple meanings and the different contexts at play in each case.

Pronunciation is often key, so you will have to mind the delivery of your sounds. At the same time, getting the hang of Japanese humor is a great way to improve your cultural immersion, and a nice icebreaker in Japanese conversations if timing is appropriate, which means you have to work on your listening and awareness skills.

Hopefully, this is enough ammunition to get you started. Enjoy and use them wisely, or you might just get the cold shoulder!

▽Subscribe to our free news magazine!▽

For more information about Japanese culture and language, check the following links!

▽Related Articles▽

▼Editor’s Picks▼

Written by

Photographer, journalist, and avid urban cyclist, making sense of Japan since 2017. I was born in Caracas and lived for 14 years in Barcelona before moving to Tokyo. Currently working towards my goal of visiting every prefecture in Japan, I hope to share with readers the everlasting joy of discovery and the neverending urge to keep exploring.